R N Bhaskar

30 March 2015

Affordable houses of 300 sq feet be provided at just Rs 3 lakh! Really? Is it possible? What about both the availability and cost of land?

The sad truth is that land was never the problem. It was always a question of political will on the one hand, and the necessity for the right policies to be kicked into place on the other. Crucial to both was the urgent requirement for a “zero-tolerance” policy relating to unauthorised squatting and incremental slum formation.

But then, politicians are always the biggest beneficiaries of slum formation. Slums allow them to create vote-banks and to distort the demographics in any given area. Hence legislators cannot be trusted to put a stop to slum development. Much, therefore depends on the role of the election commission and the courts. Unless they ensure that voting rights in cities are granted only to people who are not illegal squatters, the scourge of slum formation will remain endemic.

But let’s return to land. Can land be got for free?

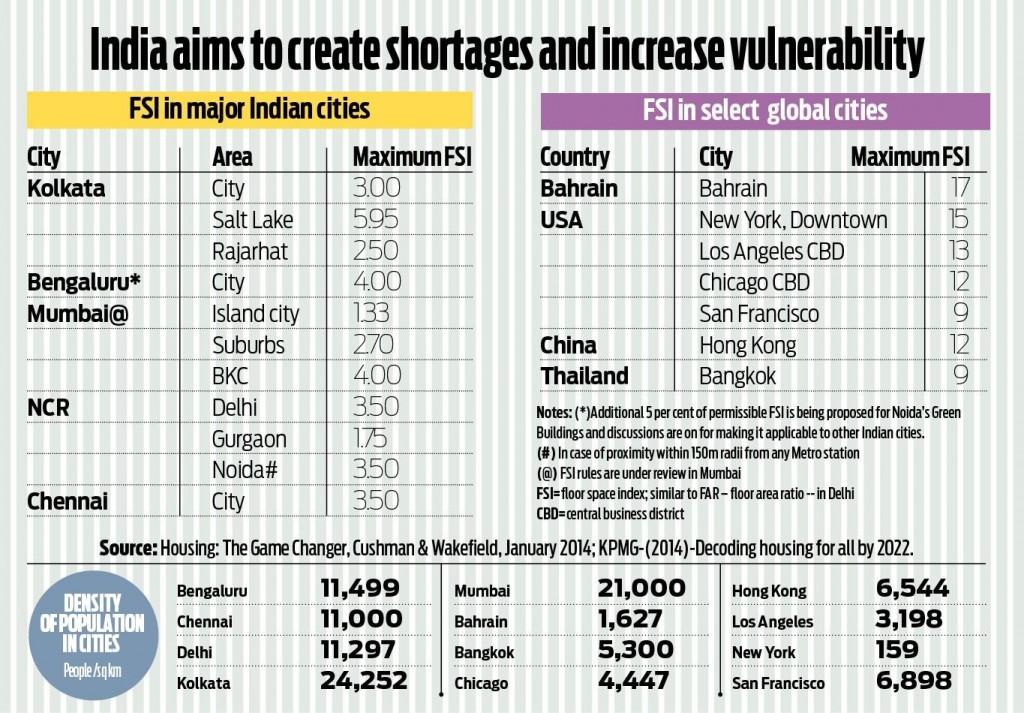

The answer lies in not looking at land, but at the availability of living space. That is indicated by the FSI, or floor space index — the ratio of living area to actual land area. But FSI can work only if two other conditions are implemented. First, it is imperative that the State creates the required infrastructure for roads, water, power lines and drainage (including sewage) disposal. It also depends on the government’s willingness to ruthlessly prohibit illegal parking, hawking or squatting.

Once these are taken care of, increasing FSI becomes the obvious solution (see table). Globally, cities with lower population densities than in India enjoy higher FSI. India — with its larger population, fewer cities, and an aspirational population moving from villages to cities — needs enhanced FSI urgently. Only that will allow huge numbers of affordable houses to get constructed before more migrants come in.

After all, urbanisation can be handled either by creating new cities, or by making existing cities go vertical.

The former is what Prime Minister Modi wants to do with his smart cities concept. That may take some time. The simpler, immediate solution is to liberalise FSI rules. A higher FSI allows for more compact cities, effective mass transport systems, sewage, water supply pipes and power cables. Sprawled-out cities are too wasteful and expensive. However, India’s legislators prefer to restrict FSI, and promote illegal slums instead.

This creates shortages and pushes up real estate prices. That benefits real estate developers (often in collusion with greedy legislators). As a result, all city dwellers get brutalised by the degrading conditions in which people live.

A higher FSI will allow governments to compel developers to enjoy this benefit only if they first utilise and deliver one-third of that space as affordable houses — for economically weaker sections — at a price not exceeding Rs1,000 per square ft. The developers can make their profits by selling ‘free’ houses, using the remaining FSI, at higher rates.

India needs to construct at least 2-5 million homes each year. Currently, the best industry estimate for affordable homes built by the private sector is just around 100,000 a year. This excludes supply from the government under its various schemes — but for which numbers are not available. The actual demand is for 18.4 million homes of which 70% is from economically weaker sections.

Unfortunately, as research from JLL (Jones Lang LeSalle) shows, more houses — almost 900,000 — are built for higher-income segments in the top seven cities each year. Sadly, even that is too little.

All this (including the politicians’ desire for demographic tinkering) results in ever expanding slums. Yet, as aspirations of slum dwellers rise, the widening gap between the living conditions of the rich and poor could easily become a major electoral issue. If the rallying war cry for the last elections was soaring unemployment, it could easily be “better living conditions” for the next elections. Beware the wrath of a disaffected population.

Experience also shows that affordable homes eventually help civic revenues to swell, as each homesteader learns to pay for water, electricity and even property tax.

But, equally important, such a policy will create many jobs. Over the past five decades, almost 40% of development investment was on account of construction. Around 16% of the nation’s working population depends on construction — around 30 million are estimated to be employed by this industry.

Employment has enormous political relevance. Do remember that one of the factors behind Prime Minister Modi’s electoral victory was rising unemployment — 60 million people looking for jobs. Since each unemployed youth belongs to a family, it translated into around 240 million disaffected voters. Such a disaffection could manifest itself again if decent homes are not available.

Significantly, once workers get trained to build better houses, there is a massive export market as well. As both the UN-Habitat and the government have confirmed, by the year 2030, an additional 3 billion people, about 40 percent of the world’s population, will need access to housing. This translates into a demand for 96,150 new affordable units every day. India can reach out to these markets. Remember, India already earns big money — $70 billion of remittances annually — through manpower exports.

But much more must be done beyond FSI. Watch this space.

The author is consulting editor with DNA.

Read the original article here.

Read more on India and its policies.

COMMENTS