Source: http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-asking-for-investments-is-good-but-can-india-guarantee-speedy-and-fair-grievance-redressal-2489553.html

Speedy grievance redressal is crucial for healthy investment flows

Much of the fresh investment into new projects has not taken off, even three years after Modi began wooing investors. Investors make conciliatory noises, but something keeps them away.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has just rounded off a speech in Davos pitching the India investment story to the who’s who of the world of business. Everyone agrees that India offers huge potential for profit and growth. But much of the fresh investment into new projects has not taken off, even three years after Modi began wooing investors. Investors make conciliatory noises, but something keeps them away. What’s going wrong?

Siren song

Nobody is willing to speak on record. But from the few statements from the government’s end, and the slew of moves one sees global investors making, the fly in the ointment seems to be in the way the government wants to protect investments from foreign investors. Many aren’t buying the government’s story as yet. The wooing of the government is quite seductive; but cautionary flags appear to be all over the place. Like the mythical Ulysses who swooned before the sirens’ songs, foreign investors love the music; but they appear to have taken precautions that they will not allow themselves to get sucked into India that easily.

Consider the remarks of two diplomats from the EU. They have told this author that they want to invest more into India, but are waiting for the logjam to clear on the international arbitration front. However, instead of taking up arguments themselves with the government both have left the negotiations to the EU, thus creating a broader front to counter the Indian government.

Then look at Japan. One would have thought that it would have pushed through investments on a war footing to complete the extremely profitable and strategically relevant Dedicated Freight Corridor (DFC), which has been languishing since 2006. The Japanese have reiterated their promises to bring in the money and even extend work on the DFC to the Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC). But for three years the money has not come in. Finally, the logjam appeared to have broken when Shinzo Abe made his latest visit to India recently. Although the government does not admit this, India and Japan have signed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) which is akin to a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). However, it covers many other fields as well. And most important is what the Japanese insisted upon – their right to approach any international arbitration seat outside India for settling any unresolved disputes. Yet, as we shall see later, despite the FTA, India has already got into a spat with Nissan. This matter has yet to be resolved.

Singapore has this clause (of international arbitration) built into its CEPA. But there are rumours that the government wants Singapore to tear up the old CEPA and sign a new one. Singapore is said to be unwilling.

So what is it about CEPA and arbitration that seems to have agitated many foreign investing countries?

Poor record of dispute resolution

The answer is simple: The government does not want to allow the bilateral investment protection treaties (BIT) it has with several countries to be valid any longer. It wants all countries to sign a clause that they shall not opt for any internal seat for arbitration outside of India until all available judicial remedies are exhausted in this country first. Almost every country has refused to sign the new clause – this includes the US, UK, countries in the EU, Japan, Singapore and Israel. It was this perhaps what Israel had in mind when Prime Minister Netanyahu said that he is still waiting for India to sign an FTA with Israel (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-thin-man-fat-man-the-israeli-army-anecdote-india-would-do-well-to-heed-2486385.html).

The answer is simple: The government does not want to allow the bilateral investment protection treaties (BIT) it has with several countries to be valid any longer. It wants all countries to sign a clause that they shall not opt for any internal seat for arbitration outside of India until all available judicial remedies are exhausted in this country first. Almost every country has refused to sign the new clause – this includes the US, UK, countries in the EU, Japan, Singapore and Israel. It was this perhaps what Israel had in mind when Prime Minister Netanyahu said that he is still waiting for India to sign an FTA with Israel (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-thin-man-fat-man-the-israeli-army-anecdote-india-would-do-well-to-heed-2486385.html).

Not that India’s record of judicial redressal is anything to be proud of (see chart). It takes a minimum of 1,420 days to get some kind of order from Indian courts for any dispute filed. Judicial redressal is a huge expenditure in India, higher than most countries in the world. And judicial processes are incredibly poor. The recent spat on how the roster of cases at the apex court should be managed is a symptom of the lack of documented processes, and the lack of the limits to which legislators (or judges) should be allowed to go.

Moreover, what worries the government most is the increasing propensity of companies using the international arbitration route through a seat outside of India to get favourable verdicts. And to understand why this happened, it is first important to take note of the events which led to this situation.

Arbitration genesis

It began with the dispute that an Australian company had with Coal India Ltd (CIL). In 1989 White Industries entered into a contract with CIL for the supply of equipment and for the development of a coal mine in Uttar Pradesh. The contract ran into disputes, and in May 2002, the disputes were referred to arbitration in London. White Industries won the award and Coal India was asked to pay White Industries a sum of USD 4.08 million.

CIL approached the Calcutta High Court to get a stay on the tribunal award seeking shelter under Section 34 of the Act, which was originally meant to only take up those issues where the arbitration award goes against a country’s laws. Unhappy with the way Indian courts had blocked an international award, White Industries approached the Arbitration Tribunal against the government in 1999. When nothing was done despite this, White Industries moved the Singapore courts against the government invoking the provisions of the Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) that India had with Australia. It contended that the damages awarded to it by the international Aribitration Court would have been part of its investment portfolio had the Indian courts not frustrated this move. The Singapore courts slapped the Government of India with a huge penalty (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2012/09/judicial-delays-hit-arbitration-awards/).

The government of India was startled at this development. Backroom negotiations probably ensured that the Singapore court verdict was not given effect. It is possible that White Industries got its payment. But the government is believed to have approached the Supreme Court to immediately review the situation. The Supreme Court issued orders on 16 December, 2011 to review Section 34 of the Arbitration Act. A five-member constitution bench was formed to examine the issue(http://www.asiaconverge.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/arbitration-2011-12-16_SC-notice.pdf).

On 6 September, 2012, the five-member bench pronounced the following: “In a foreign seated international commercial arbitration, no application for interim relief would be maintainable under Section 9 or any other provision, as applicability of Part I of the Arbitration Act, 1996 is limited to all arbitrations which take place in India (http://www.asiaconverge.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/arbitration-2012-09-06_SC-5-member-bench-bharat.pdf). Similarly, no suit for interim injunction simplicitor would be maintainable in India, on the basis of an international commercial arbitration with a seat outside India. We conclude that Part I of the Arbitration Act, 1996 is applicable only to all the arbitrations which take place within the territory of India. . . . . Thus, in order to do complete justice, we hereby order, that the law now declared by this Court shall apply prospectively, to all the arbitration agreements executed hereafter.”

The Constitution Bench had ruled that international awards from a seat outside India could not be reviewed or challenged in India courts.

Three developments, then more

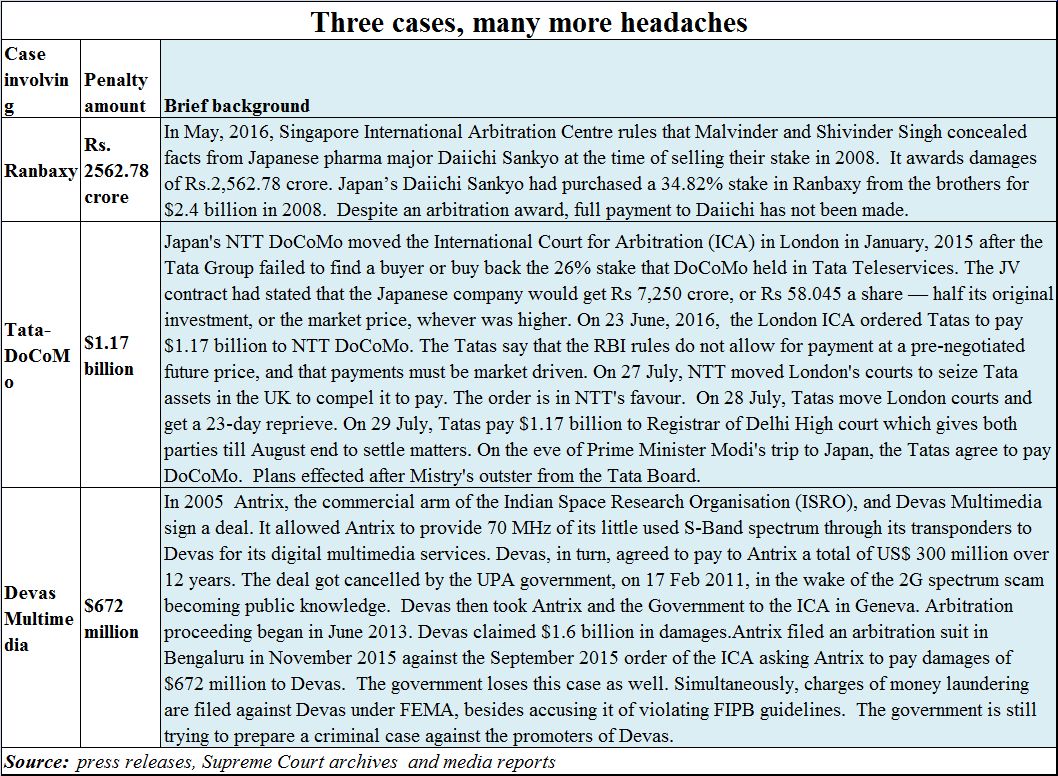

But then, once again, the law of unintended consequences began to play out. Almost all companies now began approaching arbitration courts for dispute resolution in a seat outside of India. It wasn’t long that the government was confronted with three awards that made it sit up and squirm. The most damning was the verdict in respect of the Devas Multimedia case (see chart).

While the first two related to private disputes between two companies – one Indian and the other foreign – the Devas case was a foreign company suing the government of India. Devas won the award. The government went into appeal and lost the appeal as well. Now the government is trying to build a criminal case against Devas to frustrate the international arbitration award (purely criminal matters cannot be adjudicated in arbitration courts).

While the first two related to private disputes between two companies – one Indian and the other foreign – the Devas case was a foreign company suing the government of India. Devas won the award. The government went into appeal and lost the appeal as well. Now the government is trying to build a criminal case against Devas to frustrate the international arbitration award (purely criminal matters cannot be adjudicated in arbitration courts).

That is one reason why the government now does not want any company to approach arbitration tribunals seated outside India. Its solution? It hurriedly set up an Arbitration Centre in Mumbai, and wants all arbitration matters to be settled here. But as a diplomat says, “That will make us lose the protection we have from the five-member Supreme Court judgement. Since the award will now be given by an arbitration court with its seat in India, Indian courts can still open up the award. Neither the government nor the apex court have come out with a guarantee that this will not happen.”

The government is now caught between a rock and a hard place. It does not give the Indian arbitration centre the protection that foreign seats have been given. If that were to happen, the government could lose face at home. The government does not want to be reined in by international courts, or be at the mercy of Indian courts either.

Obsessive litigant

This is because the government is itself a “compulsive litigant” (http://sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2011/30837/30837_2011_Judgement_23-Nov-2017.pdf). This was observed by none else but the Supreme Court, which stated: “Mindful of the phenomenon of the docket explosion and the rising litigation in the country, the Union of India in order to ensure the conduct of responsible litigation framed what is today known as the National Litigation Policy (NLP), to bring down the pendency of cases and get meaningful issues decided from the judicial forums rather than multiple tiers of scrutiny just for the sake of it. The Government, being a litigant in well over 50 per cent of the cases, has to take a lead in not being a compulsive litigant.”

The judgement drew its conclusions from the observations of the NLP which stated in 2010 that “Government must cease to be a compulsive litigant. The philosophy that matters should be left to the courts for ultimate decision has to be discarded. The easy approach, ‘let the court decide’, must be eschewed and condemned.” As a result, almost 50% of the 3 crore cases pending in the courts across the country are because of the government. Despite the Supreme Court’s observation and those of the NLP, the situation has not improved.

An excellent example is the manner in which – even after the CEPA with Japan signed with India — Nissan has threatened to approach the international arbitration tribunal with its seat outside of India, and the government is doing all it can to persuade the courts that Nissan should not be allowed to do this. Nissan has demanded damages of USD 770 million from the Government of India for not protecting its rights (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/nissan-sues-india-over-outstanding-dues-seeks-over-770-million-2451759.html).

That also explains why Vedanta-Sterlite has still not given up its right to take recourse to this route for its problems it faces with the government of India. And this is precisely what Vodafone too wants to do if the government does not settle its tax disputes quickly.

Lessons for India

All these disputes should teach India five lessons.

Global investors do not trust the Indian courts or the policies of the Indian government. They would prefer settlement of disputes in international courts under the provisions of the BIT as they existed till 2014.

The government of India is advised to take commercial decisions very carefully, and not push through rules with retrospective effect. Look at the way many states too want to jettison the power purchase agreements they had signed with investors in solar projects over five years ago. Just because prices are lower now does not mean that states can cast aside contractual obligations. But then India has inherited a legacy which saw the abrogation of even a constitutional guarantee to the erstwhile princely states. Having lost the Privy Purses case in 1969, Indira Gandhi waited till she enjoyed the political clout to change the composition of judges at the Supreme Court. Even this constitutional oath was thus cast aside. That – over the years — has given many legislators the feeling that political clout allows them to even dishonor agreements.

Penalise bureaucrats (their personal pockets must be affected) for going into what is today known as vexatious litigation. The sheer numbers confirm the vexatious nature of both bureaucrats and legislators.

Any attempt to tinker with India’s arbitration or BIT rules might boomerang, and send foreign investors scurrying away, but not before filing for more damages before international courts. The reliance on crony capitalism, and whimsical display of power to annul contracts could wreck India’s chances of becoming a global power.

Investments flow into areas where there is confidence in legal mechanisms. Once that confidence is gone, you will have high risk capital coming into the country, with attendant high costs as well. Those costs could cripple India permanently.

COMMENTS