https://www.freepressjournal.in/editorspick/is-the-telecommunications-sector-being-skewered

The decimation of the Indian telecom sector?

RN Bhaskar — October 31, 2019

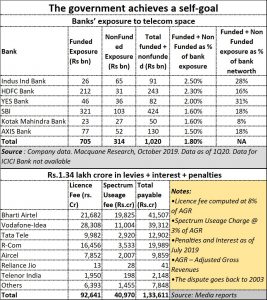

Do policymakers in India secretly harbor a death-wish? The question was uppermost in the minds of most people immediately after the Supreme Court’s ruling last week (https://clpr.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Cellular-Operators-v.-TRAI.pdf) that the telecom sector would have to pay a cumulative retrospective charge of Rs.134,000 crore (see table).

According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), banks’ exposure to the telecom sector rose to Rs 109,761 crore in August 2019, from Rs 82,034 crore in August 2017. This ties in with estimates by Macquarrie that pegged it at Rs.102,000 crore (see chart alongside).

According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), banks’ exposure to the telecom sector rose to Rs 109,761 crore in August 2019, from Rs 82,034 crore in August 2017. This ties in with estimates by Macquarrie that pegged it at Rs.102,000 crore (see chart alongside).

Banks have been saying that these debts are manageable. But they come on the top of an already unmanageable non-performing asset (NPA) problem which stood at over Rs.9 lakh crore (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/01/lessons-learnt-npa-recovery/). Add to this the risk of contagion from failures like the PMC Bank, ILFS, the Essel and Essar group exposures among other insolvency cases. India is obviously heading into financial headwinds that could be so fierce that the turbulence in the markets could be severe.

The government could have easily avoided the telecom crisis. These were results of sins of commission and omission, For instance, when the government decided to change telecom rules by first allowing additional trial periods by a new telecom operator, it could easily have foreseen the impact it would have on a sector so crucial to the well-being of the Indian economy. Ditto when it changed the interconnect rules, almost overnight. And now you have the Supreme Court ruling for which the blame can once again be put on the government.

This is because the Supreme Court merely interprets the law. But the iniquitous law was laid down, quite capriciously, by the Department of Telecommunications (DoT), an arm of the government. The DoT had been demanding interest, penalty and interest on penalty – retrospectively — on outstanding amounts.

The manner of computation has been disputed ever since 2003. Both the TRAI and the TDSAT ruled in favour of the interpretation given by the industry (though TDSAT did a U-turn subsequently). But all through, the DoT stuck to its guns, demanding more and more. DoT had exhibited this avarice first when it levied crippling spectrum charges. Then when these charges were withdrawn, and a new revenue sharing plan introduced, the DoT wanted to include even those revenues that were not strictly from spectrum useage.

And now you have the peculiar situation that — because these charges have to be applied retrospectively — the new incumbent, Reliance Jio will have to pay only Rs.41 crore, even though it has emerged as the biggest player. The other two players – Bharti Airtel and Vodafone — have to pay Rs.41,507 crore and Rs.39,312 crore respectively. The rest of the money must be written off because the telecom players themselves have ceased to exist.

Now the ball is in the government’s court. It can demand that the Supreme Court’s verdict be respected in full, with not-so-pleasant consequences. Vodafone may be the first to go belly up. This will mean that the government will get very little of its money. Nor will the banks, with ripple-effect consequences for the economy. It is quite possible that Bharti too could also end up handicapped, burdened by both debt and this liability. The winner, of course will be Reliance Jio.

But the consequences for the government will be lower money through spectrum auctions, because there will be little competitive bidding. And the huge surge of entrepreneurship and ingenuity that the market place witnessed may come to an end, because the country will be left with little competition. In that case, the government will well have killed the goose in its greed for the golden eggs.

After all, telecommunications is directly linked with economic growth. Telecom experts talk about the law of teledensity, of how economic growth and telecom penetration go hand in hand. Not surprisingly, the most advanced territories in India – Chandigarh, Daman & Diu and Delhi have a telecom penetration of 92%, 89% and 88% respectively. Compare this with some of the most backward territories of India – like Chhatisgarh, Orissa and Arunachal Pradesh which have a teledensity of just 28.5%, 33.6% and 44.9% respectively. India needs more innovative ideas to improve teledensity. More players and more competition can ensure this; not stunting the market to one or two players.

The other option for the government is to tell the DoT, not to apply these charges retrospectively, but prospectively. That would make the players healthier. It would enhance their ability to repay the banks. And the country could continue remaining a vibrant market for telecommunications. This will be more so as this sector begins to impact education health services and even media journalism.

COMMENTS