A modified version appeared at https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/milk-the-road-to-perdition-is-often-through-subsidies-5142591.html

Subsidies unmaketh the milk industry in India

Subsidies threaten an industry that can single-handedly change the fortunes of millions of dairy farmers in the country.

RN Bhaskar – 14 April, 2020

India’s milk industry – the largest in the world — is in danger of being sabotaged by both politicians and bureaucrats. This is being done by using the most seductive weapon – subsidies. To  understand why and how this is being done, a glimpse into the origins of India emerging as a milk power.

understand why and how this is being done, a glimpse into the origins of India emerging as a milk power.

Kurien’s vision

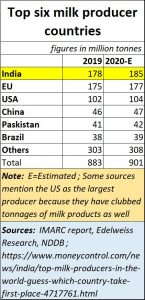

When the late Verghese Kurien ushered in Operation flood, and created the white revolution, he knew that he would make India the world’s largest milk producer. By 2000, thanks to the tireless efforts of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) India did become the world’s biggest milk producer (additional details can be got from the author’s book Game India, Seven Strategic Advantages That Can Steer India to Wealth – Penguin). Kurien knew that India could win this game provided three conditions were met

- That the farmers would continue getting the lions’ share of the market price. If the farmer got more, he would produce more.

- Imported milk should not be allowed to create surpluses in the market or sold at lower than market prices and thus adversely affect farmer-fortunes. To ensure this happened, he persuaded Lal Bahadur Shastri, the then prime minister of India, to transfer NDDB (National Dairy Development Board) to him and used it as both market maker and dairy promoter. All imported milk was to be given to NDDB which would release it gradually at market prices. NDDB would use the surplus to create a milk promotion fund. Since NDDB did not depend on government doles, and since the milk industry grew without government subsidies, both steered clear of any adverse remarks from the World Trade Organisation (WTO) which looks at subsidies as a trade distorter.

- The milk cooperatives would be aimed at maximizing the income of farmers and not of the promoters/managers of cooperatives.

To achieve all these three goals, Kurien made the cooperatives stay away from both politicians and bureaucrats. The latter therefore hated Kurien, who cheerfully returned such sentiments. Kurien was the father of the milk revolution but was despised by both politicians and bureaucrats.

All through the past seven decades, politicians have eyed the milk cooperative vote banks – farmers number over 10 million (Amul cooperatives have 3.6 million farmers —https://www.amul.com/m/organisation). That means 40 million people assuming four people to a household. This number does not include indirect beneficiaries like traders, distributors and consumers. And till Kurien died in 2012, no politician dared interfere with the workings of milk cooperatives.

The new order

The approach towards the milk industry changed thereafter. After Kurien stepped down from the chairmanship of NDDB (in 1998) his successor Amrita Patel, made changes to NDDB’s structure. She corporatized Mother Dairy, which till then was only a division of NDDB meant to provide a marketing outlet for surplus milk. She sought the status of financial institution for NDDB, when it was designed to be a milk cooperative promotional body. Politics began creeping into the milk sector.

Maharashtra’s cooperatives

Maharashtra’s cooperatives had already decided not to follow the Verghese Kurien model. They wanted cooperative promoters to have the right to decide where the benefits from milk would flow. They functioned quite differently from GCMMF where over 80% of the market price goes to farmers. The GCMMF-Amul structure became the most efficient milk producer in the world, managing procurement, processing marketing, distribution and new product creation within 20% of the market price. Other cooperatives gave barely 50% to their farmer members.

One reason was that unlike GCMMF which operates under one brand, AMUL, Maharashtra has over 60 brands. Each had its own production, processing and marketing. Second, farmers say that a

lot of milk money is used for financing politics. Third, since milk cooperatives and sugarcane cooperatives often work under the same (politician) management, they are wedded to the liquor industry too which finances politics and generates huge cash incomes. This is because sugar production leads to molasses used by distilleries. But, expectedly, all distilleries and their profits are run not as part of cooperatives but as private companies. It is the same old story – privatization of profits and socialization of losses.

Cooperatives in Maharashtra are great money generators. They run cooperative banks. Significantly, in Maharashtra at least, even the promoters’ capital of 10% in a bank is provided by the state, without even insisting on a seat on the board of directors. Thus, with no skin of their own in the game, Maharashtra’s cooperatives have learnt to play with other people’s money.

When the state government under the chief ministership of Devendra Fadnavis tried to coerce cooperatives into giving more money to milk farmer-producers, the cooperatives pleaded financial helplessness. The state then gave them a subsidy of Rs.5 per litre (the taxpayer pays, of course). But this was withdrawn subsequently, under tremendous opposition from other (non-cooperative) politicians.

Karnataka too

This state has the second largest milk cooperative after Amul/GCMMF, with 2.25 milk producers. It is believed that many of these cooperatives work under the same leadership as sugar cooperatives (Karnataka is also a big liquor producer).

Incidentally, Karnataka offers a subsidy of 20% on milk — Rs.6 per litre of milk (which is priced at Rs.30). And interestingly, while this subsidised milk invariably finds in way in Maharashtra, there has been no attempt on the part of the Maharashtra government to slap an entry tax of Rs.6 per litre on imported milk, in much the same way it does with liquor imported from Karnataka. It does point to the priorities of both state governments when in comes to milk and liquor.

Back to Gujarat

In Gujarat, cracks in the citadel that Kurien built were beginning to appear. A maverick promoter of a milk cooperative – Vipul Chaudhary – who has political affiliations with the BJP decided to break away from the Amul-GCMMF structure (https://www.businesstoday.in/current/corporate/mehsana-dairy-to-break-away-from-amul-after-46-years-slicing-10-pc-of-gcmmf-revenue/story/339527.html). Eventually he did not. The problem came when he set up additional milk processing capacity without consulting the Federation. He then began procuring milk from non-cooperative producers, which is not permitted by the Federation and cooperative rules. He then wanted GCMMF to purchase his additional milk. That was also politely refused. He then wanted GCMMF to reimburse to him losses – which he claimed were in excess of Rs.1,000 crore — which was also turned down. So, he decided to break away.

Fortunately, saner counsels prevailed. He realised that without the Amul brand, he would not be able to sell his existing milk as well, let alone the augmented capacity. He was now stuck between a proverbial rock and a hard place. So, he chose not to abandon GCMMF. It is not known whether he kept the additional cooperative capacities outside the cooperative structure. But now he had surplus milk powder – dairies must convert the surplus unsold milk into powder (SMP) to give it a longer life.

The domestic markets were aflush with stocks. So, he tried exporting SMP. But international prices had crashed. He, therefore, asked the government to subsidise his exports. Rather than give subsidies to an individual, the government decided to provide export subsidies to any SMP exporter.

The problem with subsidies

The problem with subsidies is that they distort the markets. They reward the inefficient and create pressures on the profitability of the efficient. For instance, GCMMF which is a cooperative and Hatsun, India’s largest private sector milk producer, are both extremely efficient. Both pay a large share of the market price to farmers. Both have finely honed production processing and marketing systems.

Now when they watch another producer company making the same profits (officially or otherwise) without being efficient, they feel demotivated. They too are tempted to take the subsidy route and reward their own managers, confident that this largesse will be met through subsidies.

Till now the milk industry has grown because it was free from government interference and without any subsidies. It remained healthy through efficiency and integrity. The government mustn’t allow it to become sick. After all, it is the largest in the world, the most farmer friendly organisation globally, and offers the shortest route to rural prosperity.

In places where the Amul-Hatsun-Nestle and other good and efficient players have stepped in, farmers can make a profit (income less actual expenditure) of Rs.100 per cattlehead per day for 300 days in a year (the remaining days are used to ready the cattle for the next round of insemination, and subsequent lactation).

If the milk industry becomes sick, the losers will be farmers. The government’s penchant for subsidies will ring the death knell for this immensely successful industry.

COMMENTS