https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/bangladesh-has-a-lesson-or-two-for-india-in-schooling-5289451.html/amp

The other two parts of this series can be found at :

Education #3: Watch Bangladesh – it has been doing what India forgot to do

RN Bhaskar – May 20, 2020

India needs to watch Bangladesh very closely. Especially when it comes to education.

It is significantly smaller than India. At the time it gained independence, almost everyone thought it would remain a country with a begging bowl. It had a population that was largely poor. It had hardly any industry of its own. Moreover, it was ravaged annually by floods and typhoons in the sea, Bangladesh suffered grievously in terms of money loss and more painfully loss of human lives.

But today, most countries are watching this nation. Its growth to relative prosperity has been astounding. For instance, while India is still struggling with garment exports at around $1 billion, Bangladesh has already gone beyond $32 billion. It had touched the $20 billion mark way before the financial meltdown of 2008 took place.

But today, most countries are watching this nation. Its growth to relative prosperity has been astounding. For instance, while India is still struggling with garment exports at around $1 billion, Bangladesh has already gone beyond $32 billion. It had touched the $20 billion mark way before the financial meltdown of 2008 took place.

This unexpected development is happening in the field of education as well. Contrary to popular belief that Bangladeshis are coming to India to look for jobs, the opposite has now begun to happen. Some Bangladeshis have begun moving back to their home country. Opportunities have begun to sprout there.

What is even more astounding is that, last year, Bangladesh accounted for 3,600 students from India, of which 500 were for medical studies. They had opted to pursue higher education in Bangladesh!

What this means that this tiny nation is building capacities for higher education and has even begun attracting students from India. It also means that India has not been able to build the capacities that its people need. That is unfortunate, unwise, even dangerous.

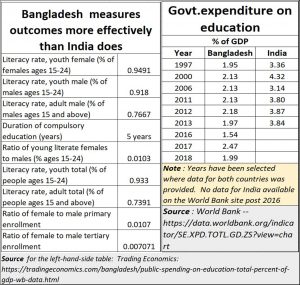

If one looks at numbers, there is no reason why Bangladesh should have performed so much better than India. It spends less on education as a percentage of GDP than does India. It spends 40% of the money allocated for education on primary education, which is what India does too. It is true that Bangladesh did spend more on primary education earlier – it was 53.74% of allocated expenses in 1993 (https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/bangladesh/public-spending-on-education). But overall, the story behind Bangladesh’s success is not the amount of money spent as much as on proper management of these funds.

That could explain why its literacy rates are higher at 74% not just in terms of numbers. This nation’s literacy comes closer to the global definition of literacy – not India’s definition. India believes that anyone who can read and write his or her own name should be defined as literate. Effective literacy in India is far lower than what is claimed. It could be close to around 40% if one goes by Pratham’s ASER findings. Its latest report (https://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202018/Release%20Material/aserreport2018.pdf) points out how, in 2018, only 44.2% of the boys in Std V could read the books meant for Std II. The score had declined from 53.1% in 2008.

The result of this poor focus on primary education in India has terribly deleterious effects on the rest of the educational structure. It compels politicians to clamour for the “normalisation” of results at the board level (std X and Std XII) examinations — in case too many students fail. They invariably do.

The presence of not-so-bring students in a classroom who cannot understand basics has a soporific effect on the rest of the students as well, and at times even on teachers. And no college can undo the damage that 10-12 years of bad education can cause to a child. It ends up in wasted years, and even unemployability (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/economy/policy/pre-budget-series-barbarians-at-the-gates-of-education-4824521.html).

So, what does Bangladesh do instead? First, it does not tie itself into knots over language. At all levels of schooling, students (not politicians) can choose to receive their education in English or Bangla. Private schools tend to teach in English while government-sponsored schools often opt for Bangla. Both students and parents thus know which language they would like their child to opt for.

Then there is tremendous decentralisation in school management. Non-government schools at higher secondary have School Management Committees (SMCs). At the intermediate college level, in the case of non-government colleges, you have Governing Bodies (GBs), formed as per government directives. They are responsible for mobilising resources, approving budgets, controlling expenditures, and appointing and disciplining staff.

A constant watch on outcomes at each level ensures that the quality of education offered is good. One more advantage that Bangladesh enjoys is that students do not have to suffer substandard teachers recruited based on reservations. There are reservations for the underprivileged at the student levels, not at teacher levels. While teachers of non-government secondary schools are recruited by the appropriate SMCs observing relevant government rules, teachers of government secondary schools are recruited centrally by the DSHE through a competitive examination.

A constant watch on outcomes at each level ensures that the quality of education offered is good. One more advantage that Bangladesh enjoys is that students do not have to suffer substandard teachers recruited based on reservations. There are reservations for the underprivileged at the student levels, not at teacher levels. While teachers of non-government secondary schools are recruited by the appropriate SMCs observing relevant government rules, teachers of government secondary schools are recruited centrally by the DSHE through a competitive examination.

Thus, one can forgive the poor investment in education – which appears to be a key reason for India’s low ranking on human capital development (see chart) – but one cannot pardon poor teaching and almost non-existent monitoring of outcomes.

Not surprisingly, one of the factors being the successful election of chief minister of Delhi, Arvind Kejriwal, was his commitment to school education. He spent 26% of Delhi’s funds on education, unlike 3.1% for the government of India. But, more importantly, he focussed on outcomes. He paid attention to parent-teacher meetings to identify and weed out teachers who did not perform well. With better management of schools, and better infrastructure (because of better funding) children have begun to learn better too. Not surprisingly, one comes across anecdotal evidence of parents who opted to move their children from private schools to (not-so-expensive) government schools. They can see for themselves that teaching there has begun to outshine teaching at private schools.

If India does not want to be left behind by Bangladesh, it must focus on primary education first. That creates more employable people, which in turns to better wealth generation. And it needs to build medical colleges and focus on merit and excellence as well. But more on this later.

COMMENTS